Inside Disney’s dramatic CEO succession saga — and the leadership lessons that changed everything

When Bob Iger walked into his first day as Disney CEO in October 2005, he inherited a mess. The company’s animation studio, the very soul of Disney, was producing flops. The board had just forced out his predecessor in a bitter proxy fight. And Steve Jobs, who controlled Pixar, wasn’t returning his calls.

Twenty years later, Iger would leave behind a company worth four times what he’d inherited, but not before watching his succession plan collapse, being forced out of retirement to fix it, and learning the hardest lesson in business: getting out is harder than getting in.

This is the story of how leadership principles built an empire, failed spectacularly, and ultimately shaped the future of the world’s most magical company.

Act I: The Empire Builder (2005-2020)

The Phone Call That Changed Everything

Iger’s first move as CEO surprised everyone. He didn’t reorganize divisions or cut costs. He picked up the phone and called Roy Disney — Walt’s nephew, who had publicly opposed Iger’s appointment and helped oust the previous CEO.

“What do you really want?” Iger asked him.

The answer was simple: Roy wanted to feel valued. He wanted Disney’s creative legacy to matter again.

Iger made Roy an honored consultant. The attacks stopped. The relationship healed.

The lesson: Relationships matter more than org charts.The belief that problems can be solved if you focus on what matters rather than operating from defensiveness.

But Roy Disney wasn’t Iger’s biggest relationship problem. That would be Steve Jobs.

The $7.4 Billion Bet

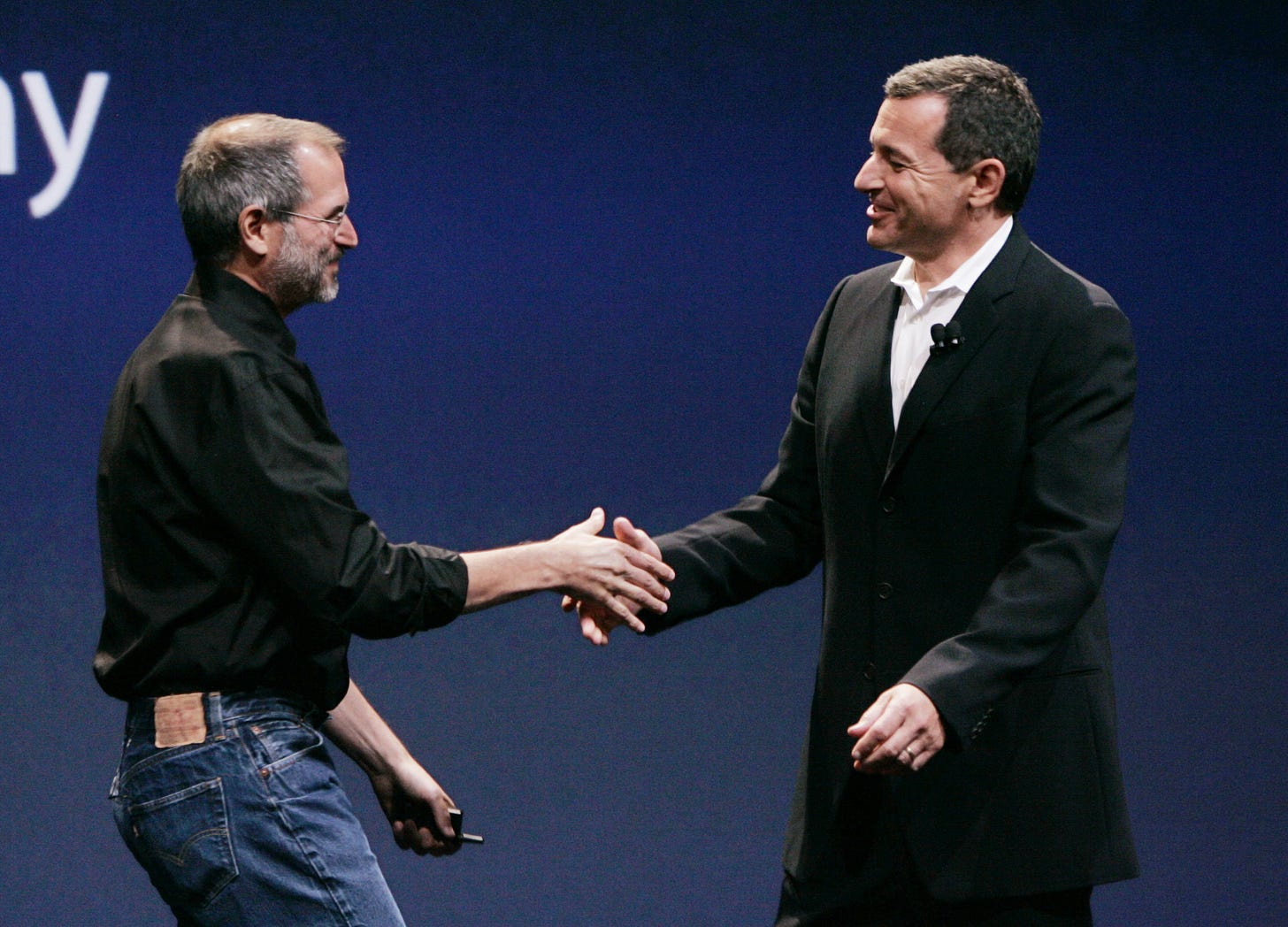

Michael Eisner, Iger’s predecessor, had feuded with Jobs for years. Their relationship was so toxic that Pixar, which had made Disney billions with Toy Story, Finding Nemo, and The Incredibles, was preparing to leave Disney and distribute its films elsewhere.

Iger had a radical idea: don’t just fix the relationship. Buy the entire company.

The board thought he was crazy. $7.4 billion for an animation studio? When did Disney already have an animation studio? Many executives worried Pixar’s edgier sensibility would damage Disney’s family-friendly brand.

But Iger saw what they didn’t: you can’t always fix a broken culture. Sometimes you need to acquire the culture you need.

He spent months rebuilding trust with Jobs. He promised Pixar could keep its culture, its team, its way of working. When the deal closed in January 2006, Jobs became Disney’s largest individual shareholder.

More importantly, other creative leaders watched how Disney treated Pixar. And they learned that Disney could be trusted.

The lesson: Great acquisitions buy talent and culture, not just assets. This embodied what Iger called the relentless pursuit of perfection — the Japanese concept of shokunin, taking immense pride in your work and instinctively pushing for greatness.

The Acquisition Playbook

The Pixar template became Iger’s formula:

August 2009: Acquired Marvel for $4 billion. Internal resistance: too edgy for Disney. Iger pushed through. By 2014, Marvel movies had grossed more than Disney paid for the entire company.

December 2012: Acquired Lucasfilm for $4.05 billion. George Lucas required delicate handling; he wanted legacy assurances and initially demanded creative control. Negotiations broke down twice. But Iger’s patient relationship-building won out. The Force Awakens made over $2 billion.

March 2019: Acquired Fox for $71.3 billion, bringing Avatar, The Simpsons, FX, and a controlling stake in Hulu. Iger’s largest and most complex bet.

Each acquisition followed the same pattern: build the relationship first, promise cultural autonomy, and integrate strategically.

Each franchise became a flywheel, box office, merchandise, theme parks, and eventually streaming.

By November 2019, when Disney+ launched, Iger had transformed Disney from a $56 billion company into a $231 billion entertainment colossus.

The lesson: Innovation requires curiosity — a deep awareness of the marketplace and its changing dynamics. Iger understood that Disney’s brand could stretch further than anyone thought possible.

The Retirement That Wasn’t

Iger had tried to retire four times. Each time, the board asked him to stay; one more acquisition, one more crisis, one more strategic priority.

By February 2020, he’d finally earned his exit. He handed the CEO title to Bob Chapek, chairman of Parks, Experiences, and Products. A solid operator. Someone who understood Disney’s most capital-intensive division.

Iger would stay on as Executive Chairman, overseeing creative strategy.

It seemed like a graceful transition. It was actually a ticking time bomb.

Three weeks later, the pandemic shut down every Disney theme park worldwide.

Act II: The Failure (2020-2022)

The Fatal Flaw

Here’s what nobody understood at the time: you cannot split authority from accountability.

Chapek had the CEO title. But Iger remained as Executive Chairman, responsible for “creative oversight.” In practice, this meant Iger still controlled strategy. Executives who’d been loyal to Iger for 15 years didn’t know who was really in charge.

As one corporate governance expert put it: “When you’re executive chair, the buck stops with you.”

Chapek bore the accountability without the authority. It poisoned everything.

The Reorganization

Chapek’s instinct was to bring order to chaos. He centralized control, overhauling the studio structure to shift power toward business distribution units rather than creative teams.

To Chapek, this was efficiency. To Disney’s creative executives, it was a betrayal.

Dana Walden and Alan Bergman — the entertainment co-chairs who’d built relationships with Hollywood’s top talent- found their authority diminished. The Imagineers, Disney’s creative engineers who designed theme park experiences, faced new restrictions and bureaucratic oversight.

The lesson: Culture eats strategy for breakfast. Chapek saw the Imagineers as a cost center to be optimized. Iger had seen them as Disney’s competitive advantage.

Where Iger had practiced — treating people with dignity and empathy, Chapek practiced reorganization.

Where Iger had championed shokunin and the relentless pursuit of perfection, Chapek championed efficiency.

The creative culture that Iger had spent 15 years nurturing began to wither.

The Walking Meetings

By fall 2022, senior executives were telling Iger the company was in trouble. Walden and Bergman felt the same. They’d voiced their concerns to the board, they said. Things couldn’t continue.

Box office returns were weak. Streaming was bleeding cash. The stock had fallen sharply from its 2021 highs.

On November 20, 2022, the Disney board fired Bob Chapek after fewer than three years as CEO.

That same evening, they called Bob Iger.

Act III: The Return (2022-2026)

The First Trading Day

Disney stock jumped 6% the morning after Iger’s return was announced. That’s how powerful the symbolic weight was — a signal to investors, talent, and the creative community that Disney was correcting course.

But symbols weren’t enough. Iger moved fast.

Within days, he dismissed Chapek’s closest advisors. He reversed the studio reorganization. He called the creative executives and asked: “What do you need?”

The lesson: Taking Responsibility means owning the mess, not explaining it away.

Iger set about rebuilding relationships with talent. In 2023, when Hollywood faced its first dual writers’ and actors’ strikes in decades, Iger negotiated patiently with both unions.

The deals cost money in the short term. They preserved relationships long-term.

The Measured Success

Under Iger’s second tenure, Disney’s streaming business turned profitable. Zootopia 2 grossed $1.7 billion globally. The parks thrived.

But the stock told a sobering story: up 22% during Iger’s return, compared to 68% for the S&P 500.

The hard lesson: Not every period produces transformational returns. Sometimes leadership means stabilization, not transformation. Iger’s first tenure produced extraordinary results partly because Disney had been undervalued. His second product produced solid results because it was already priced for success.

This is what mature leadership looks like.

And Iger knew the most important thing he could do wasn’t another acquisition. It was getting succession right.

The Process

The board, led by new chairman James Gorman (former Morgan Stanley CEO), wasn’t going to repeat the Chapek disaster. They ran succession like a major acquisition:

100+ candidates considered

Multi-year formal process

All four of Iger’s direct reports were formally interviewed

External candidates vetted

The field narrowed to two: Josh D’Amaro (Experiences chairman) and Dana Walden (Entertainment co-chair).

On February 3, 2026, they announced the decision: D’Amaro would become CEO. Walden would become President and Chief Creative Officer.

The Ending (For Now)

On March 18, 2026, Josh D’Amaro will become Disney’s ninth CEO. Dana Walden will sit beside him as Chief Creative Officer. Bob Iger will finally walk out the door — this time, apparently, for good.

Whether D’Amaro succeeds remains to be seen. The company he inherits faces genuine challenges: streaming competition, AI disruption, global political tensions, and parks that need constant capital investment.

But for the first time in years, Disney’s fundamental question isn’t about internal leadership chaos. It’s about strategy, creativity, and execution — exactly what a healthy company should be debating.

The final lesson: The best leaders build systems that transcend themselves. The D’Amaro/Walden partnership isn’t about finding another Bob Iger. It’s about creating a structure that embeds Disney’s values institutionally, so success doesn’t depend on one charismatic leader.

Bob Iger spent two decades building something extraordinary, lost it briefly to circumstance and miscalculation, fought to get it back, and is now walking away — having learned that the hardest part of leadership isn’t building an empire.

It’s letting go.