Introduction

In Part 1, we saw the fairy tales - WhatsApp sold for $19 billion, and Airbnb’s founders became billionaires. Everyone got rich!

But what happens when things don’t go perfectly? What if a co-founder quits? What if the company fails? What if you can’t sell your shares even though they’re “worth” millions?

Let’s talk about the reality of startup equity - the scenarios nobody mentions at parties, but everyone needs to understand.

Scenario 1:

When a Co-Founder Leaves Early

The Facebook: Eduardo Saverin

Remember Facebook? Let’s talk about what happened to Eduardo Saverin - the co-founder most people have never heard of.

The Beginning (2004):

Mark Zuckerberg started Facebook in his Harvard dorm. Eduardo Saverin, his friend, gave him $15,000 to help start it.

Initial split:

Mark Zuckerberg: 65%

Eduardo Saverin: 30%

Others: 5%

The Problem:

Eduardo was in New York trying to get advertising deals. Mark was in California building Facebook with the team. They started fighting about the company’s direction.

Eduardo wanted to make money from ads right away. Mark wanted to focus on getting more users first.

What Happened:

Mark and the team used something called “vesting” to reduce Eduardo’s ownership from 30% down to about 5%.

What Is Vesting?

Think of vesting like this:

Imagine your parents promise you $100, but they’ll give you $25 every year for four years. If you move away after one year, you only get $25, not the full $100.

Vesting means you don’t get all your equity at once. You earn it over time - usually 4 years.

How Vesting Works in Real Life

Meet Sarah and Tom: They start a company together, 50-50 split.

They agree to 4-year vesting with a 1-year “cliff.”

What’s a cliff?

It means you get NOTHING if you leave in the first year. After one year, you’ve earned 25% of your equity. Then you earn the rest monthly over the next 3 years.

Here’s what happens to Tom in different scenarios:

Tom quits after 11 months:

Tom gets: 0% (he left before the 1-year cliff)

Sarah now owns 100% of the company

Tom quits after 13 months:

Tom gets: 12.5% (he’s earned 25% of his 50%)

Sarah keeps: 87.5%

Tom quits after 2 years:

Tom gets: 25% (he’s earned half of his 50%)

Sarah keeps: 75%

Tom stays all 4 years:

Tom gets: His full 50%

Sarah keeps: Her full 50%

Back to Eduardo’s Story

The Result:

Eduardo’s ownership went from 30% to about 5% because:

He wasn’t showing up and doing the work

He signed agreements with vesting terms

The company diluted him through new investment rounds

At Facebook’s IPO in 2012:

Eduardo’s 5% was worth: $4 billion

If he’d kept his 30%, it would have been worth: $30+ billion

The Lesson:

Eduardo still made $4 billion, which sounds amazing. But he lost out on $26 billion because he left early and wasn’t there doing the work.

Three key takeaways:

Vesting protects everyone - If someone leaves, they don’t keep equity they didn’t earn

You have to show up - You can’t phone it in from another city

Read what you sign - Understand vesting terms before agreeing to them

Scenario 2:

When the Company Fails - Your Equity Becomes Worthless

The Harsh Reality: Most Startups Fail

Here’s what nobody tells you: About 90% of startups fail. Let’s talk about what happens to equity when a company shuts down.

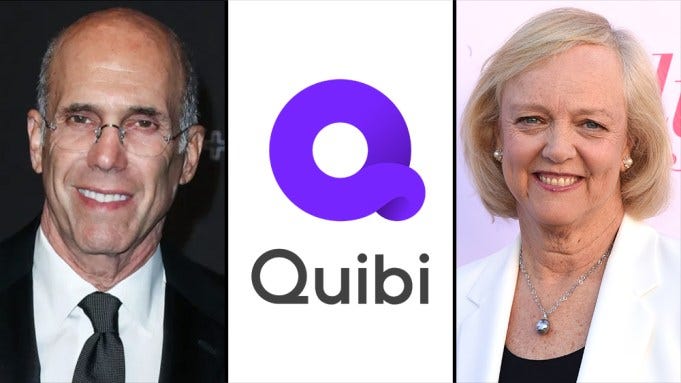

Real Example: Quibi - The $1.75 Billion Disaster

Quibi was a video streaming service started by Jeffrey Katzenberg (a famous Hollywood producer) in 2020.

The Setup:

They raised: $1.75 BILLION from investors

Big names invested: Disney, NBC, Sony

Founder Jeffrey owned: About 20%

Employees owned: About 10%

The Idea:

Short videos designed for watching on your phone. Seemed good on paper.

What Happened:

It completely flopped. Nobody used it. After just 6 months, they shut it down.

Who Gets Paid When a Company Dies?

When Quibi shut down, they sold whatever they could:

Content library: About $100 million

Technology/patents: Maybe $50 million

Total: ~$150 million

But they had raised $1.75 billion! Where did all that money go? They spent it on content, salaries, marketing, and operations.

Here’s the order people get paid:

1. Employees Owed Money (unpaid salaries, severance)

2. Banks and Loans (if any)

3. Investors (they have “liquidation preference” - they get their money back first)

4. Founders and Employees with Equity (whatever’s left... which is usually nothing)

The Math:

Money raised: $1.75 billion

Money left to return: ~$150 million

Investors got back: ~$150 million (lost $1.6 billion)

Jeffrey’s 20% equity: Worth $0

Employee equity: Worth $0

The Lesson:

When a startup fails, your equity is almost always worthless. Investors might get some money back (because they have special protections), but founders and employees usually get zero.

Scenario 3:

When Investors Want Their Money Back

Understanding Liquidation Preferences

Here’s something most people don’t know: When investors give you money, they get special rights. If things go badly, they get their money back before anyone else.

It’s called “liquidation preference.”

Example: A Disappointing Exit

Meet TechStartup Inc.

The Beginning:

Founder Sarah owns: 100% (10 million shares)

Company is worth: basically $0

The Investment (2020):

Investors give: $10 million

Company valued at: $40 million after investment

Investors own: 25%

Sarah owns: 75%

The investors negotiate “1x liquidation preference” - meaning they get their $10 million back first if the company sells.

Three Years Later: The Company Sells

Scenario A: Sells for $60 Million (Good!)

Everyone’s happy because it’s worth more than expected.

How the $60 million gets split:

Investors: 25% of $60M = $15 million ✓

Sarah: 75% of $60M = $45 million ✓

Investors more than doubled their money. Sarah made a fortune.

Scenario B: Sells for $30 Million (Disappointing)

The company is worth less than the $40 million valuation from 2020.

Investors can choose:

Option A: Take their liquidation preference ($10M back)

Option B: Take their ownership percentage (25% of $30M = $7.5M)

They chose Option A ($10M) because it’s more.

How the $30 million gets split:

Investors get their $10 million back first

What’s left: $20 million

Sarah gets: All the remaining $20 million

Not great, but Sarah still made money.

Scenario C: Sells for $8 Million (Bad)

Now it gets painful.

Investors have a right to $10 million, but there’s only $8 million total.

How the $8 million gets split:

Investors: All $8 million (trying to get their money back)

Sarah: $0

Sarah owns 75% of the company but gets NOTHING.

The “Participating Preferred” Nightmare

Some investors negotiate an even better deal called “participating preferred” or “double dipping.”

This means they get their money back PLUS their ownership percentage.

Example:

The company sells for $30 million with participating preferred:

Investors get their $10 million back first

Then investors ALSO get 25% of the total = $7.5 million more

Total for investors: $17.5 million

Sarah gets: $12.5 million

Even though Sarah owns 75%, she gets less than half the money!

The Lesson:

Not all equity is created equal:

Investor shares have special protections

Founder and employee shares don’t

When things go badly, investors get paid first

You can own a large percentage and still get nothing

Before you take investment money, understand:

What’s the liquidation preference? (1x, 2x, 3x?)

Is it participating or non-participating?

At what sale price do you get nothing?

The Bottom Line

Part 1 showed you the dream - WhatsApp and Airbnb made people billionaires.

Part 2 shows you the reality:

Co-founders can lose most of their equity if they leave early (Eduardo: 30% became 5%)

Most startups fail and equity becomes worthless (Quibi: $1.75B to $0)

You can’t sell private shares even if they’re “worth” millions (Jennifer: $2.5M on paper, $0 in bank)

Investors get paid first when things go badly (Sarah: Owned 75%, got $0)

But here’s the thing:

Even knowing all this, startup equity can still create life-changing wealth.

Eduardo Saverin still made $4 billion after getting diluted.

Airbnb employees who joined early became millionaires.

WhatsApp’s early employees made fortunes.

The key is understanding the risks and not betting your entire financial future on equity that might never become real money.

The Smart Approach:

Take a fair salary you can live on

Treat equity as a lottery ticket that might pay off

Don’t count it as wealth until you can sell it

Protect yourself with vesting and good terms

Have savings and a backup plan

Because sometimes equity becomes worth billions (Part 1).

And sometimes it becomes worth nothing (Part 2).

And you need to be prepared for either outcome.

That’s the real story of startup equity.